3/02/2022

Słów kilka o Hrabalu…

[Teatr Baj Pomorski, 29. Festiwal Jednego Aktora, 21-23 listopada 2014 roku]

„Słuchajcie, co wam teraz powiem” (s. 5) – tak zaczyna Bohumil Hrabal Obsługiwałem angielskiego króla. Zatem słuchajcie!

Wyzwanie krótkiej formy na otwarcie

Krótka forma wykładu jak ten, rocznicowego, bo w tym roku minęła setna rocznica urodzin Bohumila Hrabala, jest wyznawaniem, wyzwaniem krótkiej formy. Bo jak opowiedzieć bogactwo jego życia i twórczości w 15 minut? Jak powiedzieć tylko słów kilka? Lecz zarazem: od kogo jak nie od Hrabala uczyć się krótkiej formy? Od kogo jak nie od środkowoeuropejskiego Jamesa Joyce’a w kawałkach, puzzlach składających się na cały obrazek z wyraźnymi liniami cięcia, nie miałbym się uczyć?

Będzie to więc Hrabal marginalny, Hrabal wypisowy, Hrabal prowincjonalny, Hrabal zadumany i poważny, zatem będzie o miejscach mniej oczywistych niż gospoda U Zlatého Tygra w Pradze czy wypisy mnie znane niż kominowa scena z Postrzyżyn. Są zatem wśród nich: Nymburk i pewna deska, medytacja nad kondycją pábitela, słów kilka o Kersku i kotach, a wreszcie historia pewnego nagrobka z dziurą na głowę, i w ogóle – o śmierci.

Nymburk i deska

Google maps pokazuje, że spacer z Podebrad do Nymburka zajmuje około 1 godziny i 40 minut. Kilkanaście lat temu zajmowało mi to od godziny do całego dnia. Powody różnic czasowych były rozliczne. Jednym z nich był wszakże fakt, i stanowiło to cel każdej wędrówki, że w Nymburku znajdował się Hrabalowy browar, sprzedający piwo z budki, bo chyba kioskiem tego nazwać nie można było, a żadna poważniejsza nazwa nie pasowała, zaś cena kilku koron (i to raczej zamykająca się w 5) czyniła wyprawę malowniczą ścieżką wzdłuż Łaby wartą podjęcia, czy nawet podejmowania wciąż od nowa. Były wszakże jeszcze dwa powody. Pierwszym była deska, czyli tablica pamiątkowa dotycząca Hrabala i stryja Pepina umieszczona na budynku browaru, niepozorna, przy ziemi, tak – czego sam Hrabal miał sobie życzyć – by była na takiej wysokości, by psy mogły na nią sikać. Życzenia zostało spełnione. A że wejście na teren browaru nie było atrakcją turystyczną, wymagało zaś za każdym razem przebłagania stróża by szlaban zechciał otworzyć, tym większa zasługa w praktyce uczenia się języka czeskiego. Drugi powód był z powyższymi ściśle związany. Otóż amatorów dobrego, a przy tym i taniego piwa było zawsze wielu, a takie okoliczności sprzyjają gadulstwu, czy by pozostać wiernym językowej tradycji Hrabala – pabitelstwu. Tak pobierana nauka chyba nie poszła w las, skoro dziś Państwu o tym opowiadam.

Pábitel i medytacja

Czym zatem jest pabitelstwo? Kim jest pabitel? Pabitel najlepiej czuje się w czeskiej hospodzie (a czy są inne?), siłę czerpie z piwa przepijanego panákami, żywiołem jest słowo, słowo mówione, słowo prawdziwe, gdyż jego własnego, choć nie musi być prawdziwe w sensie filozoficznym, prawdziwościowym, nie musi być też prawdziwie jego własne. Liczy się wszak to, że to on opowiada. Pod budką z piwem – jak to wszak w polszczyźnie brzmi? – w Nymburku pabitelstwo kwitło, my młodzi hrabalowcy z różnych stron świata zgromadzeni na kursie języka czeskiego wraz z nim.

Tam żywioł dominował nad strukturą, słowa na tekstem, prawda na sensem, doświadczenie nad refleksją. Bachtinowskie „żywe słowo” w – jak mówią Rosjanie – „żywym życiu” musi dominować, a nasza praktyka językowa wyraźnie na to wskazuje. Pabitelskie gadanie posługuje się „żywym słowem”, wciąga nas w sam środek i serce świata mówionego, w którym jedno nie wyklucza drugiego, a to drugie kolejnego, i tak bez końca.

Pabitelstwo jest demokratyczne, choć dominuje jeden, ten który opowiada. Pabitelstwo jest egalitarne, ale jak w każdej kulturze oralnej, słowa mówionego, wiadomo kto stanowi elitę, lokalną, zawsze tylko taka bowiem być może, ale elitę. Czy pabitelstwo kwitnie w czeskich hospodach wciąż? I tak, i nie. Trzeba wiedzieć, którą wybrać. Ale nie zdziwcie się Państwo, jak miast gadulstwa znajdziecie zadumę, miast karnawałowej (znów Bachtin!) zabawy i frenetycznego szaleństwa ciszę i spokój, przetykaną niekiedy dzwonieniem automatów do gier (zwłaszcza w hernach) i współczesnej muzyki, miast kolektywnego przepijania – indywidualne popijanie. Ale przecież i tę zadumę w prozie Hrabala spotkać można na każdym kroku, prawdziwie Kartezjańską medytację, czy raczej – myśli Pascala.

I oczywiście każdy z Państwa, czytelników Hrabal, doskonale rozpoznaje ten opis jako idealnie pasujący do jego pisarstwa, do snutych przez jego narratorów i bohaterów opowieści, często sprawiających wrażenie strumienia świadomości (znów Joyce!), właśnie żywiołu słowa mówionego. Lecz to powierzchowne powinowactwo jestpowinowactwem z wyboru, wyboru autorskiego. To pułapka, którą Hrabal na nas zastawił, wciągając nas w swe opowieści. Książki wycyzelowane, dopracowane, nawet jeśli zmieniane powielokroć – jak Zbyt głośna samotność – to zawsze będące kreacją literackiego geniuszu. Stuk maszyny na dachu Hrabalowej chaty w Kersku wyznaczał rytm jego poetyckiej zawsze prozy.

Kersko i koty

Kersko to dziś imprezy firmowe i integracyjne, spanie w bungalowach i … turystyczna ścieżka śladami Bohumila Hrabala. Na przełomie wieków był tam spokój, Hrabala już oczywiście nie spotkałem. Choć kto wie? Chaty, czeska odmiana dacz, ukryte w lesie, wciąż jeszcze wtedy ciążące bardziej ku epoce minionej niż rozbuchanej transformacyjnej rzeczywistości egzotycznych, a na pewno śródziemnomorskich wyjazdów, nie miała w sobie nic interesującego. No chyba że trafiło się do znajomych na chatę. Tam pabitelstwo rozkwitało na nowo, ze wszystkimi tego konsekwencjami.

Tam Hrabal ze swoimi kotami przebywał, tam z Pragi dojeżdżał by je karmić. Wtedy jeszcze one wciąż tam były, między drzewami (a może w wyobraźni?), a przez płot jego dom można było zobaczyć: szarawy, zapuszczony, z wyblakłymi zielonymi okiennicami, płaskim dachem, rdzewiejącą zieloną bramą, nieciekawy, mijany, stojący nieopodal głównej drogi, w bocznej alejce schowany. Dziś tabica turystycznego szlaku nie pozwala go minąć.

To kocie poświęcenie, ta kocia opiekuńczość, to kocie oddanie, jakby na przekór ludzkiemu światu, wraz z oddalaniem się, odchodzeniem z tego świata, świadomie, konsekwentnie, jak w jego pisarstwie, jak w passusie zamykającym Zbyt głośną samotność, gdzie wielki czeskie, siedemnastowieczny myśliciel, Jan Ámos Komenský przegląda się jak w zwierciadle:

„Każdy miłowany przedmiot jest środkiem Rajskiego Ogrodu, i ja, zamiast pakować czysty papier pod Melantrichem, otóż ja jak Seneka, jak Sokrates, ja w mojej prasie, w mej piwnicy wybieram swój upadek, który jest wyniesieniem, choć suwak prasy wgniata mi już nogi pod brodę i jeszcze bardziej, lecz ja się nie dam wygnać z mojego Raju, jestem w swojej piwnicy, z której nikt mnie już wygnać nie może…” (s. 118)

I prasa do zgniatania makulatury, wraz z ulubionymi książkami, zgniata bohatera, który – jak wciąż nam powtarza – trzydzieści pięć lat pracował w tym miejscu.

I kończy ostatnim przebłyskiem umierającej świadomości: „Siedziałem na ławeczce, uśmiechałem się prostodusznie, niczego nie pamiętałem, niczego nie widziałem, niczego nie słyszałem, ponieważ byłem już chyba w sercu Rajskiego Ogrodu” (s. 119).

Hradištko i pamięć

Cmentarze mówią nam pewnie więcej o żyjących niż o zmarłych, lecz – który to już raz? – w przypadku Hrabala jest pewnie odwrotnie. W Hradištku pochowany na niewyróżniającym się cmentarzu, ma wyróżniający się nagrobek. W nim, dosłownie: w nim, choć przez chwilę każdy może stać się Hrabalem. Wysoki prosty blok, z otworem wielkości głowy, gdzie każdy może stanąć za nagrobkiem, zaś jego twarz ukaże się… No właśnie: gdzie? W Hrabalu? W grobie? W wieczności? W Rajskim Ogrodzie? I ta ręka, prawa, jak u lalki, choć nie barbie (prędzej malostrańska Bambino di Praga – to też Hrabal! – z Kościół Matki Bożej Zwycięskiej), lecz bardziej muskularna, doczepiona do tego pomnika, ręka pisarza, ręka pisząca. Kolejny Hrabalowy detal, wciągający nas z niesłychaną intensywnością w jego świat.

Przykłady? Proszę bardzo. Trzy. Smakowite:

Pierwszy poetycki z Adagio lamentoso:

„Na pełni księżycowej błyszczą pierwsze kroki Armstronga,

mnie jednak bardziej przejęła wiadomość w popołudniówce,

jak to sześćdziesięcioośmioletnia zielarka przysnęła

na łące i została wessana przez kosiarkę,

po czym z maszyny wypadł trup wraz z sianem i ziołami” (s. 142)

Cóż za wyobraźnia! Błyszczące pierwsze kroki Armstronga na pełni księżycowej w połączeniu ze śpiącą (na wieczność dzięki kosiarce) zielarką.

Drugi może jednak z Postrzyżyn:

„W ciągu tygodnia Francin wypił (…) jeszcze z pewnością pół hektolitra letniej białej kawy i na całej ścianie rozwiesił wypisane piórem ze stalówką redis numer trzy i opracowane graficznie slogany: (…) KTO DO GOSPÓD NIE CHADZA, / NIE JE I NIE PIJE, / WŁASNE ZDROWIE ZDRADZA!” (s. 113-114.

I trzeci, erudycyjny, ze Zbyt głośnej samotności:

„…raczej jednak zajrzałbym na Smichov, tam w szlacheckim ogrodzie jest pawilon, gdzie w podłodze jest guzik i jak ktoś go nadepnie, to ściana się rozsunie i wyjedzie woskowa kukła, całkiem podobna do tej z Kunstkamery w Petersburgu, gdzie jak sześciopalczaste monstrum księżycową nocą nastąpiło niechcący na guzik, to wyjechał siedzący woskowy car i pogroził mu, jak to pięknie napisał Jurij Tynianow w Woskowej personie” (s. 107-108).

Zatem detal, szczegół, opis skoncentrowany na wybranych punktach naszej rzeczywistości, niekiedy jakby w krzywym zwierciadle odbijającym świat na swój sposób, jedne elementy uwypuklając, inne rozmazując, czyniąc niedostrzegalnymi. Bo Hrabal to wielki mistrz świata, oddawanego z mimetyczną doskonałością, lecz i we własnym poetyckim języku. Pamiętajmy bowiem, że u Arystotelesa mimesis miało być nie tyleż wiernym odzwierciedleniem świata w realistycznym tego pojęcia rozumieniu (choć nic nie stoi na przeszkodzie by tak było), co prawdopodobnym, czyli takim, które odpowiada przyjętej poetyce. Jedyny warunek miał polegać na tym, by w ramach wybranej konwencji, świat był prawdziwy, by logika wewnętrzna dzieła nie zawodziła. U Hrabala prawda, jego prawda, jest immanentnie wpisana w dzieło. Jak mówił „Piszę zawsze o tym, co godnego uwagi przydarzyło się mnie, o tym, co godnego pozazdroszczenia przydarzyło się innym. Zatem punkt wyjścia jest zawsze autentyczny, na początku zawsze jest zdarzenie, przeżycie” (Auteczko, s. 5).

Wyznawanie intelektualne na zamknięcie

Drodzy Państwo, mnożyłem przed Państwem intelektualne tropy (Arystoteles, Bachtin…, by poprzestać na początkowych literach alfabetu) i wpuszczałem Was w retoryczne pułapki, Hrabala zaś dzieliłem na części pierwsze, dodawałem kolejne konteksty i własne doświadczenia (czy prawdziwe?), odejmowałem zaś zbędny balast komentarzy, by równanie wskazało na… No właśnie? Na co? Czy raczej: na kogo? Na Hrabala, oczywiście. Matematyka, nawet w tak precyzyjnie skrojonych tekstach nie działa. Życie nie poddaje się, choć – jak Hrabalowe wyjście ze świata przez okno na piątym piętrze szpitala Na Bulovce 3 lutego 1997 roku, co też przepowiedział sobie w Czarodziejskim fleciew 1989 roku, pisząc: „ileż to razy chciałem wyskoczyć z piątego piętra” (s. 148) – to my poddajemy się życiu. I, jak zawsze, śmierci. W Czarodziejskim flecie ratował go anioł stróż, ściągając go z parapetu (s. 148-149). W życiu anioła zabrakło.

Choć i tu Hrabal dawał receptę, czy klucz do (z)rozumienia. Słynne jest zakończenie Pociągów pod specjalnym nadzorem z Oskarowej wersji filmowej w reżyserii Jiřígo Menzla, gdy główny bohater, Miloš, pada zastrzelony przez niemieckiego żołnierza, choć pociąg ostatecznie wybucha. Sukces? Książkowe zakończenie jest wszakże ciekawsze, bogatsze, albowiem Miloš umierając mówi do ucha zabitego Niemca: „Trzeba było siedzieć w domu na dupie…” (s. 93). Zatem porażka.

I ja również, kończąc przyznać się musze do porażki. Jako bohemista, slawista, zajmujący się intelektualną historią Czech od lat, jak mam sobie z Hrabalem poradzić, który wije się jak piskorz i umyka wszelkim kategoryzacjom? Przeczytać go, czy raczej – czytać go wciąż na nowo („by od czytania już nigdy nie móc spać, by od czytania dostać dreszczy”; Zbyt głośna samotność, s. 9), prze-żyć, doświadczyć (Czech? Czechów? Czeskości?) to jedno (jak sam mówił: „biorę piękne zdanie do buzi i ssę je jak cukierek, jakbym sączył kieliszeczek likieru, tak długo aż w końcu ta myśl rozpływa się we mnie jak alkohol”; Zbyt głośna samotność, s. 7), jak wszakże zrozumieć?

Z tym pytaniem, bo jednak nie z Pociągowym… zakończeniem, i z tą porażką, Państwa pozostawię. Jak pisał bowiem Hrabal w Jednym zwyczajnym dniu, i w pełni mogę się pod tym podpisać: „ja teraz doceniam, że los jest silniejszy niż wszystkie nasze starania” (s. 27). Zapraszam zatem na wystawę i przedstawienie, na które los nas zaprowadził, i nasze niepozostanie w domu. Dziękuję bardzo.

Literatura cytowana – teksty Bohumila Hrabala

Adagio lamentoso, przeł. Józef Waczków, w: Rozpirzony bęben. Opowieści wybrane, wybór i przekład Józef Waczków, Warszawa; Czytelnik 2000, s. 139-146.

Auteczko, przeł. Jakub Pacześniak, Kraków: Znak 2003.

Bambino di Praga, przeł. Józef Waczków, „Literatura na Świecie”, numer specjalny pt.

Hrabal, 1989, s. 4-14.

Czarodziejski flet, przeł. Józef Waczków, w: Rozpirzony bęben. Opowieści wybrane, wybór i przekład Józef Waczków, Warszawa; Czytelnik 2000, s. 147-158.

Jeden zwyczajny dzień, przeł. Andrzej Jagodziński, „Literatura na Świecie”, numer specjalny pt. Hrabal, 1989, s. 16-29.

Obsługiwałem angielskiego króla, przeł. Jan Stachowski, Warszawa: PIW 2000.

Pociągi pod specjalnym nadzorem, przeł. Andrzej Czcibor-Piotrowski, Izabelin: Świat Literacki 2002.

Postrzyżyny, przeł. Andrzej Czcibor-Piotrowski, Izabelin: Świat Literacki 2001.

Zbyt głośna samotność, przeł. Piotr Godlewski, Izabelin: Świat Literacki 2003.

(Toruń, listopad 2014, dodany w lutym 2022)

17/10/2021

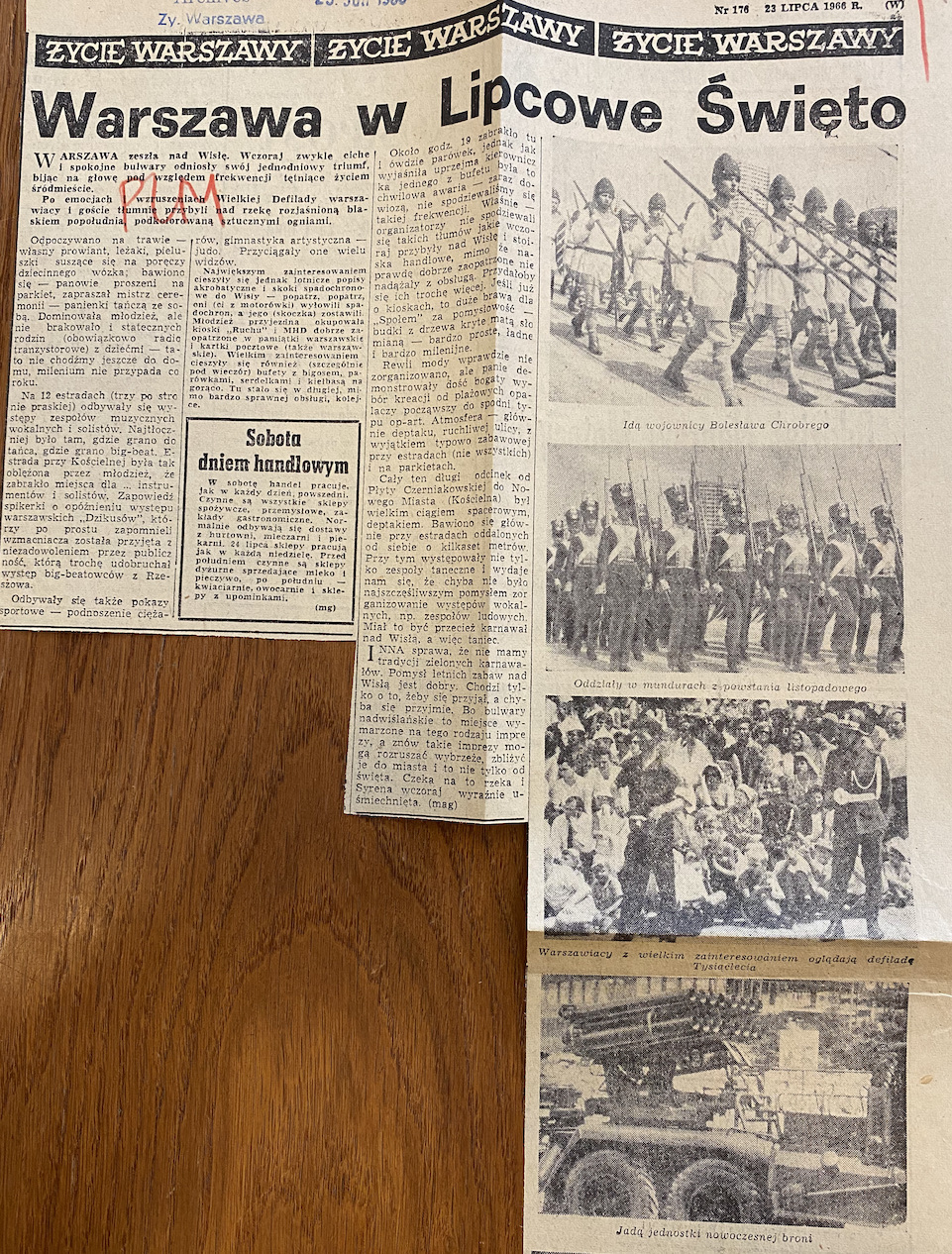

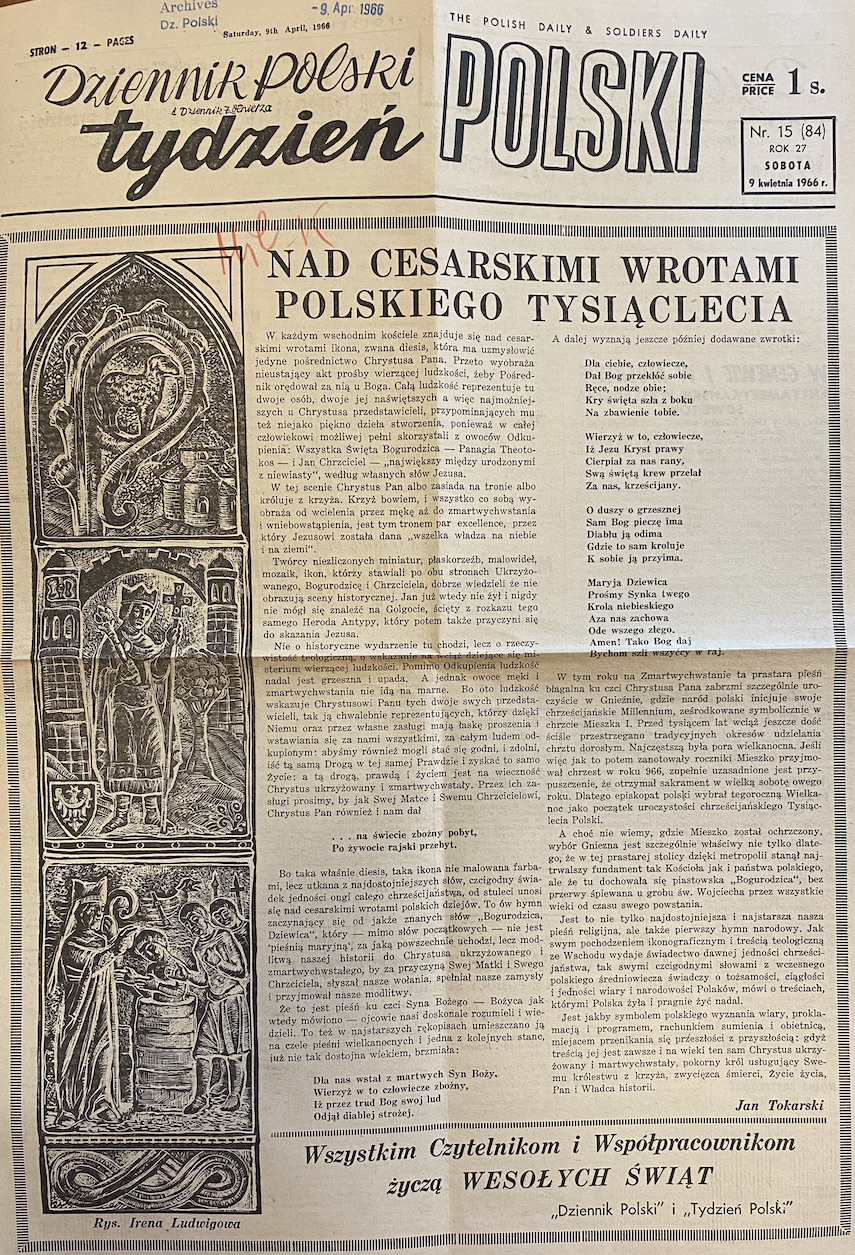

Anniversary Celebrations in Central and Eastern Europe

From the nineteenth to the twenty-first century, lavish celebrations of various anniversaries were essential elements of creating modern national identities in Central and Eastern Europe and the historic politics or politics of memory (Geschichtspolitik) of particular states.

Although our project concerns the celebration of the millennium of Christianity in Central and Eastern Europe, it may have a broader dimension. Such celebrations are part of a particular model of creating a modern community—corresponding to the current needs of a state, a nation, and a religious group.

The focus of our interest will be the influence of such anniversary celebrations on the culture of particular countries or nations of Central and Eastern Europe as well as the opposite perspective: the form (and content) adopted by (during) these events, based on a specific cultural model. Another essential element of our research will be the transnational dimension and cross-fertilization between countries. Such transnational cooperation or borrowing took place within transnational institutions, e.g., the Catholic Church, or involved ideological collaboration, e.g., the one occurring within the Eastern Bloc. Finally, the idea of anniversary celebrations fits perfectly (and conceptually extends) the notion of “inventing tradition”.

Various kinds of celebrations, anniversaries, commemorations, parades, and state and church ceremonies played a significant role in all those millennial projects. They are an essential part of what Terrence Roger and Eric Hobsbawm once called “invention of tradition”. In the cases they analyzed, it was a matter of “inventing” nations or states, strengthening them, symbolically solidifying them, and making the politics of memory more coherent. Similar mechanisms can be found in celebrations of anniversaries: they are not contradictory to history, but neither are they a study of the past. They do not adhere to facts nor are their reconstruction; they are a game and spectacle prepared for the needs of the present. They can refer to what happened centuries ago—it is a convenient starting point, which gives a stimulus for strictly academic research—but they are aimed at contemporary audiences and have political goals.

In our project, we are interested in both the cultural background of such celebrations and their political role. The context is, of course, the transition from a pre-modern (or early modern) society to a fully modern one. And in this sense, it is a process of a broader nature. It is not related only to the post-1989 transformations in Central and Eastern Europe. We can find it earlier in the modernizing societies of Western Europe and somewhat later in the decolonizing communities of the world.

In the case of Central and Eastern Europe, however, such celebrations are associated with the ongoing processes of the emergence of modern nations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and nation-states in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The history of anniversary celebrations can be inscribed in the history of politics of memory, the building of national identities, the marriage of Church and state (and sometimes mutual competition), as well as in the presentation of specific (e.g., national) values or (political) beliefs.

One of the least researched and, at the same time, most significant events of this kind were the so-called millennium celebrations associated with the millennium (often symbolic) of the official adoption of Christianity. This is our specific focus within the grant.

* * *

The photographs illustrating the blog entry come from the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives. Collection HU OSA 300-50-1, Radio Free Europe (RFE/RL Research Institute), 50 Polish Unit, Box 6 (image 1), Box 1897 (image 2).

This blog post is the result of the research project "Millennium. Celebrating the anniversary of the baptism of Eastern and Central Europe-comparative analysis" (OPUS 16, No. 2018/31/B/HS2/02917) funded by the National Science Center. Details about the project are available on the website https://millennium.umk.pl/pages/main_page/?lang=en

(Haarlem, October 2021)

13/07/2021

Politics of memory à rebours. A short sketch about Andrzej Stasiuk’s latest book “Przewóz” [“Carriage”; Wołowiec: Czarne 2021, pp. 400, hardback ISBN 978-83-8191-174-0]

All of us are said to be peasants, but forgive the generalisation at the beginning if you are not. Andrzej Stasiuk made us wait a long time for his fictional prose and struck a chord of national-patriotic sensitivity. He has accustomed us to his journeys along the wilderness of Europe and, increasingly often, of the East. Who has not travelled to Babadag? But whoever looks beyond or before his travel prose will remember “Dukla” – one of the most beautiful prose poems in contemporary Polish literature. He often described Polish and Central European post-communist transformation from the bottom up. He tenderly drew portraits of the invisible and the unheard. He drew maps of a forgotten Europe. His prose was full of light and space, human faults becoming the only signs of memory. Beskid Niski – a mountain range in southern Poland – could not have found a more sensitive or tender narrator.

Stasiuk’s “Przewóz” [“Carriage” – a working translation] has everything you would expect: the province, ordinary life, the “transformation” which is already underway but which is de facto to come; but also a kind of living truth. There is also a surprise. The whole thing takes place at a significant moment in World War II, on the Bug River, just before the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. We meet Poles from the borderline of cultures, with all the languages, religions, traditions that existed. There are Jews in hiding, decent Germans, and Soviets across the river. And anxiety hanging in the air, cut only by senseless violence, whose main perpetrators are candidates for future so-called “cursed soldiers” [“żołnierze wyklęci”]. Or maybe they are just ordinary bandits who want to take part in this war. They use violence against people in hiding, each other and animals; they do not have enough courage for a real fight, either against the Germans or the Soviets. This is just a declaration, a word, a boast. All the more significant is the voice of the Polish writer because “cursed soldiers” have become one of the primary symbolic historical references of the right-wing authorities, as well as of the associated extreme right-wing and nationalist circles, including - hooligan football fans. Both the official state narrative of the current government and the presence of references to these armed groups in popular culture are pillars of building the politics of memory in Poland. In opposition to this, the left in Poland tries to show their bandit and criminal character, which is following the knowledge of professional historians in this area. Grandmother Marysia, who comes from Białystok, used to tell stories about how bands of pseudo-partisans, who were in fact neighbours’ sons, robbed, raped and murdered, not in the name of any fight for freedom but in the name of short-term profits and desire to get rich. It is no different in Stasiuk’s book, although even this last element is not crucial. More important is their absolute powerlessness, a kind of armed impotence in the face of a natural enemy, a constant playing the game for the sake of their security. Stasiuk’s vision is, therefore, something more than just politics of memory à rebours to the dominant right-wing discourse. It is a negation of the whole idea of praising both armed heroes and anti-heroes.

The gallery of characters is vivid, expressive, sparingly sketched, with significant roles for women, the real protagonists of this war. Female characters turn out to be particularly important in Stasiuk’s work. They are the real ones - experiencing real emotions, fear, and showing real strength, courage, and wisdom. They are as if out of the world of the hitherto dominant female war characters. They are not presented in a sugary-sweet, naïve, stereotypically vulnerable mode, but they do not immediately become comic-book superheroes either. They are painfully honest in their strength and drive to survive. I don’t think anyone else has portrayed women of war the way Stasiuk did in his latest book.

All this is interspersed with Stasiuk’s contemporary journeys to the land of his childhood - real and reminiscent, alone and with his father. He comes across the ruin of his family cottage, and the descriptions of the destruction of the house, its colour, are very much to the taste of all chatterers. Memory has a physical name here. His memory is linked to the ruined farmhouse he knows from his childhood and to which he revisits. The old house triggers memories, reactivates images and stories of older generations. The entire war is in Stasiuk’s mind made up of stories told by the elders - sometimes overheard and misunderstood, sometimes directly absorbed as children. Today it acquires meanings and senses, while the literary form makes the memories alive for the reader.

Finally, about smells: if his earlier books were visual, this one is full of smells, sometimes stinks. The sense of smell goes wild here, and the nose is thrown into imaginative ecstasy and disgust. Every scene has its smell; every person is depicted sensually; the food – though simple – reads as if we were looking over the cook’s shoulder; the nature at the turn of spring and summer explodes with scents. This is an extraordinary journey, one that makes you want to close your eyes and absorb the world with senses other than your eyes.

(Strzyga - Toruń, May - July 2021)

09/22/2020

St. Wenceslaus' Millennium

Exactly 91 years ago, on September 22nd—which was a Sunday—the celebration of St. Wenceslaus' Millennium began in Czechoslovakia. It initiated a whole series of similar celebrations in Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th century. Croatia (as a part of Yugoslavia) was supposed to be the next, but World War II put a stop to these plans. In Poland, preparations began in the 1950s and culminated in 1966. The celebrations were marked by a struggle between the Catholic Church and the communist state over hearts and minds of the people. The Croats returned to the idea of celebrating the millennium in the mid-1970s, but this time the Great Novena (which lasted for a decade) turned out to be a prelude to the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia, revolving around a historical and civilizational dispute between Croats and Serbs. Finally, at the end of the 1980s, one of the most surprising Millennium celebrations took place—the anniversary of the baptism of Kievan Rus’, where the dispute between Kiev and Moscow marked the direction of spiritual changes in the perestroika era. In all these cases politics turned out to be less important than the religious dimension.

The Millennium celebrations in one of the least religious countries in Europe, Czechoslovakia, had a different character. For many, it was surprisingly both a religious and a state event. The official part lasted only for a week. According to the plan, a procession of children started at Hradčany and ended with a meeting of the children with the president of the republic Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk [TGM] in the castle gardens. For the following days, different events were scheduled. However, the purpose of these celebrations seems clear, and so does the nod to religion, which may be surprising in the non-religious TGM state. The aim was to unite the young state, inhabited by three main language groups—Czech, German and Slovak—and including even more numerous religious or ethnic groups, with Jewish, Hungarian and Orthodox communities being fairly sizeable. The idea of creating a modern political nation above and beyond religious or ethnic identification required not only grassroots work and economic development but also a symbolic sphere. The Millennium celebrations were supposed to have a unifying character; they mobilized politicians, clergy, writers, journalists, intellectuals, but also ordinary citizens. The myth of the community found its symbol, its history, thus consolidating the language of images beyond divisions. It turned out later that it was not a permanent solution, and that the divisions could not be easily overshadowed. Nevertheless, when the children met with the president in the royal gardens on September 22nd, 1929, they could not yet know this.

Today, therefore, it is ideal to publicly inaugurate the year-long project “Millennium. Celebrating the anniversary of the baptism of Eastern and Central Europe—comparative analysis”, funded by the National Science Centre (OPUS 16, No. 2018/31/B/HS2/02917). The team consists of Agata Domachowska and Łukasz Gemziak with Adam Kola as the PI. The project is part of the research conducted by the University Center of Excellence ‘Interacting Minds, Societies, Environments’ (IMSErt https://imsert.umk.pl/en/ ) and the Laboratory for the Study of Collective Memory in Post-Communist Europe (POSTCOMER http://www.postcomer.umk.pl/ )—both institutions operating at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun.

The project website will start soon. Keep an eye on the progress of our work.

(Prague, September 2020)

22/07/2020

Memory Studies for the Future. Remembering (COVID-19) as Survival Value

Our memory is a sign of the past. Collective or social memory stores what has passed and for some reason is vital to the community. As such, the politics of memory is a tool of political struggle and social engineering. Undeniably, the collective memory of humanity will keep the coronavirus pandemic in its resources. In some countries or regions, it will become an essential element of building a community. It will be so in the memory of those living in the age of COVID-19, it will also survive in the next generations—in the form of post-memory2 or social traces of disease preserved in works of art. It will also become an essential element of scientific development. It seems that never before in history such great resources have been allocated for one scientific and social purpose at the same time3. Even the most significant military projects, with the Manhattan Project at the forefront, cannot compare to this. Nor have so many scientists ever switched their activities on a global scale just to make COVID-19 collapse, as well as to seek a remedy for illness, economic crisis, social and mental problems. There is no room here to talk about the inequalities that the pandemic has uncovered, but their scale is overwhelming.

Can memory studies do something today in the context of the coronavirus pandemic? Is there any sense in reaching for tools and conceptualisations developed within their framework? Can we think about memory for the future? Are the memory studies helpful here?

More on the blog of The Center for Interdisciplinary Research (ZiF – Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Forschung ) of Bielefeld University: https://zif.hypotheses.org/809

There the full text, as well as texts by other authors, focused on the COVID-19 issue.

(Toruń, May-June 2020)

07/07/2020

The Kościuszko Statue in Washington, D.C., and why we should leave graffiti on it

During the Black Lives Matter protests, the statue of the Polish-American hero from the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817) in Washington, D.C., standing near the White House, was sprayed with BLM slogans. In the right-wing media, not only in Poland, a wave of hate towards the protesters after the death of George Floyd poured out. The slogans were aimed at Donald Trump and included other anti-racist postulates of the movement. The Polish right-wing immediately picked up the tone of the American president. However, it soon turned out to be a misguided choice, as Kościuszko's heart was instead beating on the left. And a surprising idea quickly emerged: to leave graffiti on the monument as a sign of history and shared memory.

When history happens before our eyes, we are usually speechless in commenting on it. Twitter culture requires conciseness, the world of live media coverage has radically accelerated, the only history seems to be lagging behind. The lockdown has slowed everything down. And it seemed that it would stay that way. Already some countries were introducing more and more far-reaching restrictions, and a new form of government—the COVID-19 authoritarianism (as in the case of Hungary, or the Law and Justice politicians ruling in Poland, dreaming of Budapest on the Vistula Riverbank). But the murder of George Floyd by a policeman turned everything upside down. Also thinking about memory. It turned thinking about memory towards the future. And perhaps in new ways of thinking about sites of memory.

Kościuszko's defence against vandals, as the protesters in the Polish media, were called, concerned the glorious past. Indeed, here it was a full agreement that it was difficult for the protesters to choose a worse object to express their political will than Kościuszko. At the same time, however, it may be challenging to find a better purpose for such a political demonstration in the United States. If we had the opportunity to talk to our predecessors, it might turn out that Kościuszko is satisfied—with these inscriptions on his own monument.

Kościuszko is rightly considered a hero of the United States and Poland. In the United States, he took part in the American War of Independence. He contributed to the victory in the battle of Saratoga. He is, among others, the builder of the West Point fortification. In the American army, he reached the rank of Brigadier General. In recognition of his merits, he received 500 acres of land from the Congress and salary. The money was later used to buy out and educate the slaves, and Thomas Jefferson entrusted the execution of his will. Its overtones leave no illusions about its abolitionist character. But its implementation leaves much to be desired.

After his return to Poland, Kościuszko took part and commanded the fights for independence in Poland, which was losing it as a result of the partitions. He became famous for the fact that, contrary to the nobility's standards, he partially abolished the serfdom of peasants in his own estate. It was a breakthrough in the thinking of the nobility at that time. They did not like such deviations from accepted laws and customs. When in 1794, as part of the uprising, the so-called Kosciuszko Uprising, he based his troops on peasants (the so-called "kosynierzy"—from scythes placed on a storm serving as weapons for the fighters) and on riflemen's forces modelled on the American Rangers. And although the uprising lost, the invaders finally took Poland, Kosciuszko's modern thinking is present in modernist Polish thought. Thus, it is difficult to find here a biography of a hero for the Polish or American right.

In this short biography, it is not difficult to find such elements that indicate that in BLM, he would not be on the side of the state administration, but on the bottom of the protesters. It would not be so surprising, considering how the statue presents itself, if we think other stories of the Polish struggle "for our freedom and yours". One of them was the support of the Haitian Revolution (then Saint-Domingue) at the turn of the 18th and 19th century, which led to the creation of the first state that was free of both slaveries and ruled by non-white citizens. Moreover, the Haitian Constitution stated that the country would be independent and could not be inhabited by white people. There was one exception—for Poles. To suppress the revolution, Napoleon sent armed troops to the island, including the Polish Legions—emigration armed forces. However, he did not take into account the fact that while French soldiers would fight in the name of France, Polish soldiers would go to the side of rebellious slaves. Their descendants still live in Haiti—among others in the village of Cazale. Thus, in Polish thought (and action) at the turn of the 18th and 19th century, more situations have nothing to do with today's attempts to seize the past by the conservative right.

This history helps to understand why the dispute over Kościuszko's memory and the graffiti on his statue is essential. It shows that the left has and can have its traditions, just like the liberals. We are not condemned to the dictum of right-wing traditionalism. We are not doomed to think about the past from one perspective only.

An idea has emerged in Poland (and an internet petition signed by doctors of the sociology and political philosophy, Łukasz Mol and Michał Pospiszyl) to keep these inscriptions on the monument. I fully agree with that. Of course, this is a subversive vision of what memorials or monuments are supposed to be. However, if they are to be something more than just historical monuments restored from time to time, under which official delegations sometimes place flower wreaths, then there is no better opportunity to change our thinking about memory. It will stop being hostage to the past. It will become a message for the future.

This exciting idea to leave these graffiti on the monument—a historical sign of these BLM events and histories. I would say that it is a palimpsest of memory—a deep entanglement of different layers of history (Kosciuszko, slaves, serfs, Haiti, where Kosciuszko never was, George Floyd, BLM), which makes sense here. Or a multi-directional memory in the spirit of Michael Rothberg, connecting worlds and times. Despite hypocritical politicians.

(Toruń, June 2020)